I’m not moaning, you don’t hear me moaning

These are the words spoken by Gladys Morris, the artist’s dead grandmother, that form, along with other snippets of her conversation, the soundscape for moving image artist Andrew Kotting’s latest work The Woman of Kent, a short film that acts as an intervention in the cinema space at Kino Digital in Hawkhurst, Kent.

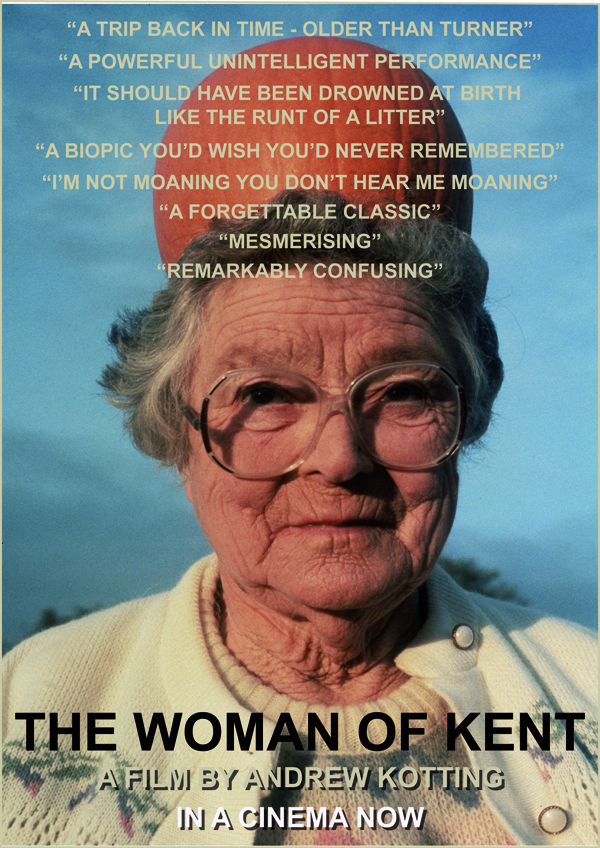

The Woman of Kent interrupts the cinematic experience like an explosion. The words of Gladys are laid over tiny sections of archive moving image showing a Kent that no longer exists, edited together at high speed and interspersed with contemporary pinhole stills of the cinema as it is today. The film will be shown exclusively at the Kino, before regular screenings. The audience may notice the accompanying poster designed by Kotting in the foyer, advertising it as ‘remarkably confusing’ and ‘a forgettable classic’, but other than this will receive no indication of what they are about to witness.

The film teases us about our constructions of the past and present. Silent black and white footage of early 20th century people at work or play is cut up and edited by Kotting, then presented as a barrage of moving images thrown at the screen at high speed. Gladys’ voiceover constantly pulls us away from any romantic ideal of the past that may be suggested by the footage of soft-focussed vistas and sped-up limb movements borrowed by Kotting from the vaults of Screen Archive South East. It brings us firmly back to the often strange realities of her life in Kent, the literal backdrop for the film. Though her intonation suggests her place in history, the sound recording is clear and crisp, and it is impossible to wear the equivalent of rose-tinted glasses when listening to her monologue. At the same time the here and now is presented in the film as a still pinhole camera image, thus reducing our vivid colour-image saturated present to the simplest of photographic devices. It is quiet and empty in these still cinema images, the view taken from the screen towards rows of empty seats, turning the camera lens’ gaze to the audience, presenting yet another twist on our perspective.