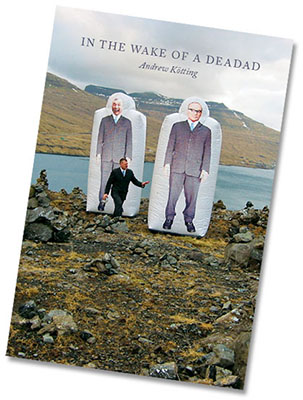

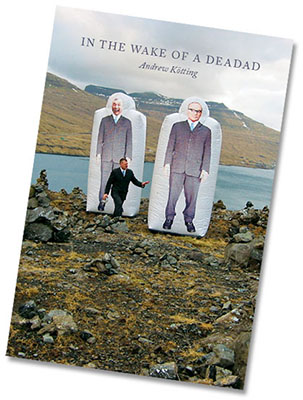

The

Book

The

book is available directly from Andrew

Kötting(£30 including postage

and packing UK only). It can also be bought from LUX ONLINE

-------- Book excerpts ---------

So I set

about sending out an invitation to write to 65 invitees, (one for each

year of his life):

-----------------------

INVITATION

This is an invitation to participate in a work provisionally entitled

In the wake of a dad dying

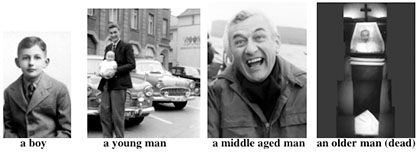

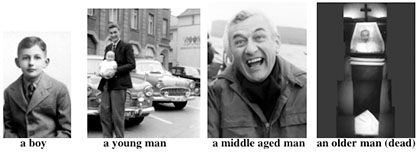

At the bottom

of the page are four photographs of my dad, who is now dead. He was born

on 31st January 1935 and died on 14th December 2000. The first is a photograph

of him as a young boy the second is of him as a man, the third is of him

as a middle-aged man and the last one is of him as an older man, (dead).

I am interested

in trying to compile a portrait of him through the words or marks of other

people. To this end I would be very pleased if you could spare the time

to provide me with “something” about my Deadad. Some of you

will know him, some of you will know about him and some of you will not

know him at all. Some of you won’t even know me. Whilst writing

about my Deadad I would like you to consider a series of questions, (consider

them but disregard them by all means).

Hence some of

the questions might be: What do the pictures tell you about him? What

was his point of view? What did he use to do? What did he want to say

but didn’t? What gave him pleasure? What were his principles? What

was his greatest fear?

Confabulation

is encouraged and there is no prescribed length or size to the work generated.

A pencil is enclosed as a somewhat peppercorn token of my appreciation

for your time and possible energy.

Yours sincerely

Andrew Kötting

-----------------------

I was attempting

to glean a more objective insight into what-who this man might have been

and use some of the replies as an inspiration for my own contemplations

on his-my life and death.

Smidgens

from some of the replies:

….

I think it was the deadgrandad who was a kraut in England at the time

of the war, and some kind of military he was, and as they didn’t

trust the devious köttingkraut, they posted him on the faroes where

he would watch the grey sea for uboats, and, I suppose, wonder what strange

path had led him there, from Deutschland to England to this funny island

with its own language, somewhere farflung in the grey sea, where they

like nuffink better than to tuck into a whale yum yum taste the blubber

on that ….What did he give you, the deadad ? he gave you a name

with an umlaut, which is a major bequest, of which I am most deadenvious.

Wot would I give for an umlaut, to be höpkins..o twould be an marvellous

thing to be sure. For as you know, I know that fing that few brits know,

namely that krautlfings are the best fings around….

Ben Höpkins

…. Erase the human presence and the photographs hold their interest:

(1) A boy’s jacket.

(2) Cars parked outside a European building. (Vehicles, number plates,

heraldic mural, columns of an arcade.) This is not Bexhill, an earlier

life. A young father, angular with potentialities.

(3) A section of boat, a misty jetty.

(4) The cross and coffin.

The story has a clear trajectory, already we know too much of this man,

the dignity of a life in its free-falling predestination. Follow the wavy

line of those elevated eyebrows and a small possession occurs. I don’t

know what happened, but the spirit explodes from the open mouth. The box-boat

slides into an ocean of flame. The man wakes.

Iain Sinclair

….

Your father – full of hope as a child, over sensitive, too much

hurt by the world, and so prone to lashing out, frightening to a child,

I imagine. Terrified of being unloved, and hopeless at making himself

loved. But then all fathers are like this, astonished to find themselves

fathers at all, having to play the role of persecutor when they were born,

like all children, to be the persecuted. And your father my contemporary,

was brought up in a pre-Freudian world, where there were no models for

fatherhood, or any acceptable by a contemporary world.

Fay Weldon

….

I’ve got my nose about an inch from the photographs as I write this.

Wish Andrew had sent clearer ones. A French writer I like, Roland Barthes,

invented the word “punctum” to describe what I’m looking

for in these photos of you. He explain: “A photograph’s punctum

is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant for

me).”

We are getting to the bruising bit, the fact that you who are so alive

or, rather, who is coming alive before my eyes as I look and hear your

voice and type, are no longer alive. That is big time bruising. I can

feel it coming.

Mark Cousins

….

However, in a way, it might be said that Mr Kötting is trying to

be iconoclastic in his approach to his father. He is not trying to discover

the truth about him, the depths of his father’s feelings and emotions,

his relations with his family and friends. He is not even really trying

to come to terms with his own emotions, his own feelings towards his father.

I doubt that he will ever be able to discover his own feelings through

compiling “a portrait through the words or remarks of other people”.

It may, of course, be that Mr Kötting, by inviting answers to his

questions, is attempting to philosophise about the meaning of life in

general and trying to comprehend what it means to be a human being. It

may be that he is trying to surpass his own personal feelings, faults

and limitations in order to see humanity as a whole.

Gregorios

Archbishop of Thyateira and Great Britain

Jem Finer

Seen

through photographs, people become icons of themselves

Portraits in life and death, Susan Sontag